By James Doughney, Victoria University

The loss of international students due to COVID-19 restrictions, and predicted second semester declines, will see universities lose between A$3 and 4.5 billion, according to Universities Australia.

The higher education sector was dealt another blow this week when the government said universities wouldn’t get the increased access to the A$130bn JobKeeper fund for registered charities.

Universities estimate more than 21,000 jobs are at risk in the next six months, and more after that.

On April 3, Prime Minister Scott Morrison said about international students:

If they’re not in a position to support themselves, then there is the alternative for them to return to their home countries.

This was chilling in its indifference. The Commonwealth has good reason to support universities hit by falling international student revenues as part of its pandemic stimulus measures.

Current university jobs depend on this revenue. According to a Deloitte Access Economics report commissioned by Universities Australia, universities contributed A$41 billion to the Australian economy and supported a total of 259,100 full-time jobs in 2018.

The government also has good reasons to support international students who have lost jobs and are not eligible for JobKeeper or JobSeeker payments.

Read more: JobKeeper payment: how will it work, who will miss out and how to get it?

International students in Australia contribute more than just the fees they pay. They also spend money while they are here, generating jobs and income in the broader economy.

In fact, the international education sector has become so economically significant that to burn it now will dampen Australia’s post-pandemic recovery.

Just how significant?

Since 1985, when the Commonwealth allowed Australian universities and colleges to charge full rather than subsidised fees, revenue from international students has grown exponentially in real terms, flattened only briefly by the GFC.

Exponential is a familiar term in these pandemic days. It’s another way of talking about compounding – growth on growth. The blue line in the below chart on Australia’s education exports is exponential.

Total education exports – as Australia’s national accounts categorise them – comprise both the fees international students pay and the amount they spend on goods and services while in Australia.

Chart one

Education exports as we know them today had grown from near zero in the 1970s to about A$37 billion last financial year (2018-19). In 2018-19, they comprised almost 40% of Australia’s exports of services and 9% of exports of all goods and services.

By comparison, Australia’s total rural exports to the world were about $44 billion last financial year.

Read more: The coronavirus outbreak is the biggest crisis ever to hit international education

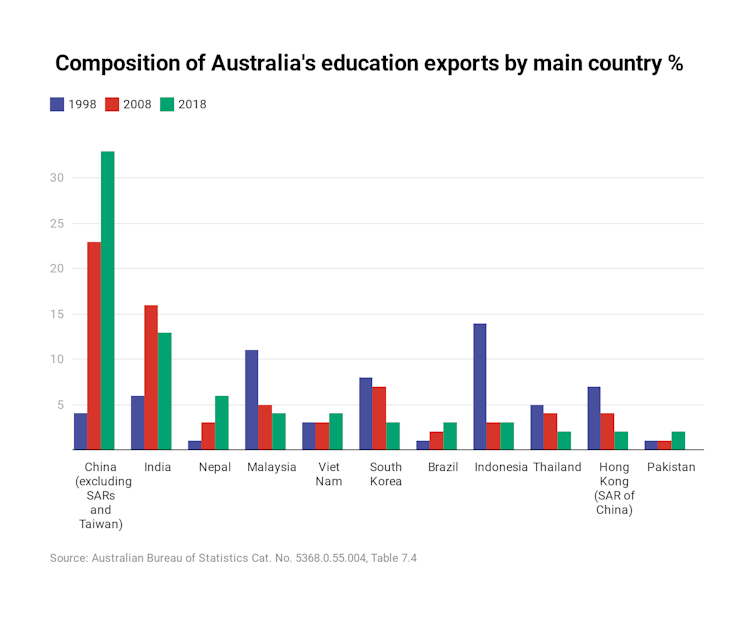

Universities are scrambling to determine the size of the inevitable international student decline they will experience. For instance, on March 1, 2020 56% of international student visa holders from China were outside Australia, and Chinese students account for one-third of total education exports.

Chart two

From 2003 to 2018, international onshore student revenue rose, on average as a share of all universities’ revenue, from 14% to 26%. For some universities, the dependency is even greater, well exceeding 30%.

Overall student revenue also grew, both as a share of, and by a larger proportion than, total revenue. Neither the Commonwealth’s funding share nor spending by universities on academic teaching have kept up. The latter has fallen as a share of student revenue from 37% in 2003 to 30% in 2018.

Chart three

What the government should do

Education minister Dan Tehan’s message to international students will win few friends. On the one hand it says “you are our friends, our classmates, our colleagues and members of our community” and allows those who have been in Australia for longer than 12 months access to their superannuation.

Cynically it adds that where we need you (such as in nursing and aged care), we will let you work more than your allowed 40 hours per fortnight.

And no JobSeeker payments, even for those here for more than a year, but merely access to what must be piddling superannuation accounts, is a shocking way to treat “our friends” and “members of our community”.

Considering the amount of money these students have brought in to our economy, giving them access to JobSeeker payments would benefit us all.

Read more: 3 ways the coronavirus outbreak will affect international students and how unis can help

Higher education also requires a nationally coordinated policy response of its own – not just one that ties it in with other measures.

The government should consider reintroducing demand-driven funding, which operated between 2012 and 2017. Under this system, universities could enrol unlimited numbers of bachelor-degree students into any discipline other than medicine and be paid for every one of them.

Restoring this policy is especially important in the light of an inevitable increase in domestic students that will follow this pandemic, and rising unemployment. Dan Tehan has signalled more support is in store for domestic students, but it’s not clear whether demand-driven funding will be restored.

Giving universities access to the same JobKeeper status as charities, who are eligible if they have experienced a 15% revenue reduction, makes sense. It would mean universities would be better placed to support their most vulnerable employees, namely the huge proportion of casual teaching, research and administrative staff on which they rely.

Universities will downsize

Without adequate government support, universities will be forced to shrink, with job losses likely occurring in proportion to the decline in revenue. Universities’ expenses have grown broadly in proportion to their total revenue.

It hasn’t been as if the growth in international student revenue was quarantined and devoted to particular purposes. These were just bundled up with domestic student revenues and funded growth.

In the absence of a nationally coordinated response for the sector, reduced revenues will also have disproportionate effects. Some universities have the cash reserves to absorb losses, shrink and, as it were, ride out the storm.

Poorer universities are not in such a position. Some might not have the cash reserves to permit an easy reduction in size. If forced by insufficient support to contemplate redundancies, their liabilities will increase and some might fail.

James Doughney, Emeritus professor, Victoria University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.