Nicole Gurran, University of Sydney; Madeleine Pill, University of Sydney, and Sophia Maalsen, University of Sydney

Despite the cooling property market, affordable rental housing remains in critically short supply across Australia. Unable to get a private rental unit or social housing, many low-income renters must resort to informal and insecure accommodation. These range from share homes or rooms, to dwellings that breach planning or building regulations.

Our newly released study sought to shed light on this problem. We found more people are living in shared rooms or dwellings, often in uncrowded and unsuitable conditions. And illegal dwellings are on the rise in Sydney.

Read more: Tracking the rise of room sharing and overcrowding, and what it means for housing in Australia

What is informal housing?

“Informal housing” usually costs less because it breaches planning, building or tenancy rules, or offers residents few protections under these rules. Examples include unauthorised or illegally constructed dwellings, as well as informal rental agreements, like share housing or room rentals.

Wherever there is a shortage of affordable housing or barriers to access, a market for informal alternatives will emerge.

In Australia’s major cities, low-income earners, recent migrants and international students face particular barriers to getting affordable rental housing. These groups often face discrimination, lack rental references or or may fall prey to international agents who offer inadequate accommodation at inflated costs.

Read more: Room sharing is the new flat sharing

In England, illegal “beds in sheds” are a well-recognised problem. In parts of the United States such as California, unauthorised dwellings may contribute around 5% of new housing supply.

No similar estimates exist in Australia. Our standard housing indicators – new dwelling completions, rent and sales data, as well as five-yearly Census changes in tenure – conceal the informal and illegal arrangements that proliferate in unaffordable markets.

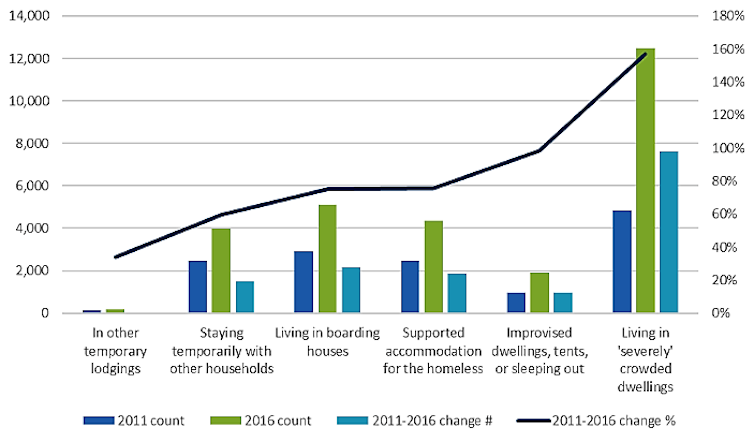

Homelessness growth in Greater Sydney by classification, 2011-2016

More are resorting to informal arrangements

Informal arrangements like renting a room in someone’s home or sharing with friends have always been part of Australia’s housing system.

Living in a share house might well be a rite of passage for young people. Sharing well into adulthood and into retirement is a different matter.

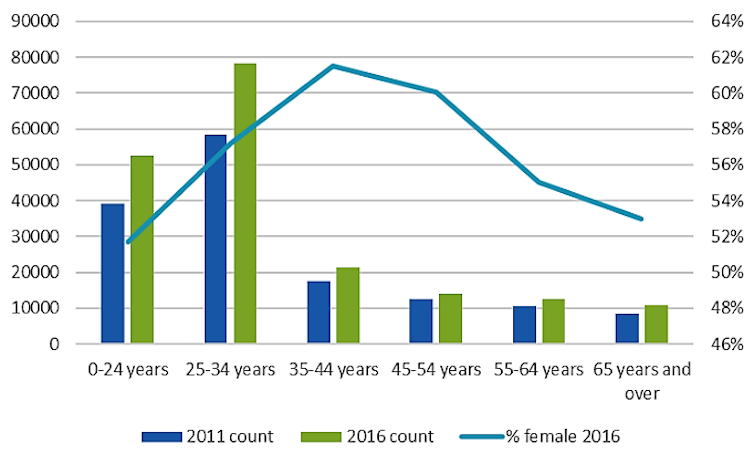

Share housing in the Greater Sydney region increased across all age groups above 24 years old between 2011 and 2016, according to the ABS Census. Those aged over 45 now amount to 20% of sharers. In particular, many more older women are sharing because they lack the means to own their own home or rent independently.

Greater Sydney share households (persons) by age group, 2011 and 2016, and % female 2016

Read more: Generation Share: why more older Australians are living in share houses

For our study, we interviewed council building inspectors and tenant support workers serving inner and southwestern Sydney. We also examined informal housing types emerging within suburban neighbourhoods.

Our study found the types of share accommodation are changing. As well as few legal protections, sharers often live in uncrowded and unsuitable conditions, where conflict between residents becomes more likely. Tenants informally renting rooms or secondary dwellings from onsite owners report uncomfortable feelings of surveillance and insecurity.

Read more: Overcrowded housing looms as a challenge for our cities

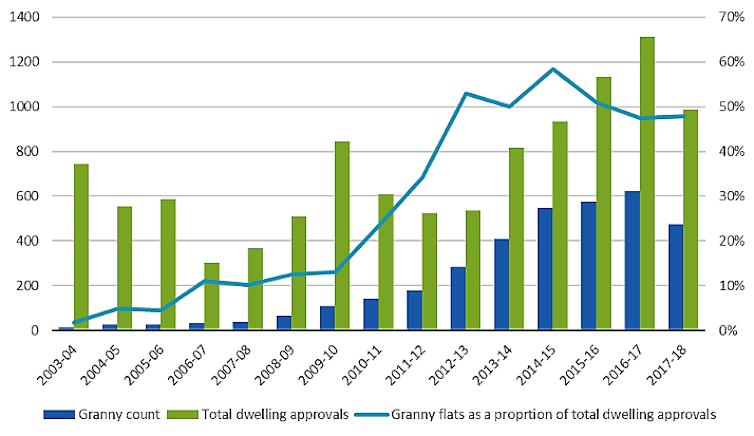

Secondary dwellings, or “granny flats”, are often viewed as a flexible or informal housing type. Unlike other states, New South Wales planning law encourages these developments as a form of affordable rental supply. This offers a sensible relief valve in Sydney’s tight housing market.

But in some areas – such as Fairfield – granny flats have come to dominate new housing development.

Secondary dwelling development and proportion of all dwelling approvals in Fairfield

This is because “codification” – fast, often privately certified approval for compliant applications – has made granny flats a low-cost option for home owners who want to increase the utility of their properties. Landlords see secondary dwellings as a low-cost, high-yield investment.

But it’s unclear whether these secondary dwellings are being rented out as lower-cost accommodation and, if so, whether they are an appropriate and secure rental housing option in the long term.

Read more: When granny flats go wrong – perils for parents highlight need for law reform

Illegal dwellings on the rise

One problem our study focused on was the growing incidence of illegal dwellings in Sydney. These include secondary dwellings that are built, or converted from a garage or shed, without planning permission.

These arrangements can be very dangerous. Unsound construction, inadequate or absent insulation, ad hoc electrical wiring, and poorly drained sites expose occupants to serious health and safety risks. The invisible nature of informal housing increases fire risks – with emergency response staff less likely to suspect people are living in a garage or outbuilding.

Illegal dwellings may be more accessible for lower-income earners and others facing rental discrimination. But they are not necessarily low cost. Our study found evidence of illegal granny flats being advertised for over $300 a week. A building inspector commented: “There’s nothing affordable about paying good money for rubbish.”

A lot of resources are needed to identify and remove illegal dwellings. Building inspectors usually become aware of illegal dwellings through complaints from neighbouring residents. Participants in our study described the problem as endemic, as local government lacks the resources for proactive enforcement strategies.

Informal housing solutions?

Informal housing is not necessarily exploitative or dangerous. In fact, it can offer solutions beyond prevailing models of private or public housing provision. For instance, self-organised housing cooperatives or “deliberative” developments are promising alternatives to private rental or ownership. But these remain niche options in Australia.

Read more: Supersized cities: residents band together to push back against speculative development pressures

The message from our study is that the informal housing sector needs to be recognised and monitored within the wider housing system. Measures to improve security and living conditions for occupants, and to ensure informal dwellings comply with planning rules, are critical.

Structurally, it’s essential to remove the barriers to private rental experienced by lower-income and vulnerable groups. As many others have argued, this means adequate funding for social and affordable housing, inclusionary planning to ensure affordable homes are included in new developments, adequate resourcing for tenant advice and crisis services, and further tenancy reform.

Read more: Co-housing works well for older people, once they get past the image problem

Nicole Gurran, Professor of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Sydney; Madeleine Pill, Senior Lecturer in Public Policy, University of Sydney, and Sophia Maalsen, Lecturer in Urbanism, School of Architecture, Design and Planning, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.