By Joshua Gans, University of Toronto

I totally support the goal of eliminating the coronavirus from Victoria and at the same time hopefully eliminating it from all of Australia.

I’ve written a book making the case this is the best way to get Australia back to normal given the uncertainty of the timeline for a vaccine and the difficulty of continually managing a pandemic.

But an examination of the modelling the Victorian government has used to justify an extension of Melbourne’s Stage 4 lockdown for a further two weeks suggests its deficiencies might have driven the results.

A different, more traditional, model would have suggested a more granulated location-based (e.g., local authority or post-code group) easing of restrictions achieving the same result with fewer economic and social costs.

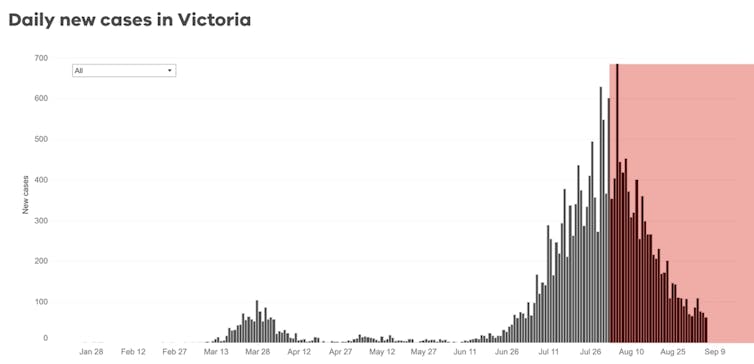

There can be no doubt the Stage 4 lockdown, introduced at 6pm on Sunday August 2, has achieved spectacular results.

Usually in an upswing, measures take two or more weeks to have an effect. But in Victoria the decline was dramatic.

That doesn’t mean costs don’t matter. The delays inherent in the extension and reopening plan are considerable. It works like this:

Step 1 announced on Sunday extends the Stage 4 restrictions for an extra two weeks but with some small extra freedoms. These include:

- moving the start of the nightly curfew from 8pm to 9pm

- allowing two hours of exercise, up from one

- allowing outdoor public gatherings of two people or one household

- creating “social bubbles” for single people who live alone and single parents with children under the age of 18

- reopening playgrounds.

Steps 2, 3 and 4 are all subject to health advice, and depend entirely on daily new case numbers going down.

If new cases meet the required thresholds, Step 2 may begin on September 28 allowing:

- public gatherings of up to five people from a maximum of two households (for a maximum of 2 hours and within 5km of home if you’re in metropolitan Melbourne)

- staged return of some students to school, and child care reopens

- more workplaces can reopen

- outdoor pools can reopen and personal training sessions with up to two clients allowed

- outdoor religious gatherings with five people and a leader allowed.

Step 3 could look like this from October 26:

- curfew abolished, no restrictions on reasons or distance to leave home

- up to 10 people can gather outdoors, and you can create a “household bubble” with one nominated household allowing up to five visitors from that household at a time

- more progression on school years 3-10 returning

- hairdressing, retail and hospitality can reopen conditionally

- a staged return to outdoor, non-contact sport for adults (outdoor contact sport for under-18s is allowed).

And from November 23, subject to all the necessary requirements, Step 4 includes:

- allowing up to 50 people to gather in public and up to 20 visitors at homes

- hospitality to reopen with limits, retail and real estate to reopen

- up to 50 people at weddings and funerals (20 in a private residence)

- further return to community sport.

The trigger for Step 2 is fewer than 50 new daily cases on average over two weeks, while the trigger for Step 3 is only five new daily cases on average over two weeks and zero mystery cases over the entire two weeks. For Step 4, the trigger is zero new cases state-wide for 14 days.

There are some good, progressive things about this plan. Schools are opening relatively soon, and before pubs. Playgrounds are opening quickly and allowances are being made for social bubbles. And big gatherings are last.

The issue is: why is the pace of reopening so slow?

One reason could be that the government is trying to avoid disappointment of things being extended. But playing those games seems second order to providing clarity. It seems to me the plan is slow because it relies on the outcomes from some modelling.

So let’s look at that modelling.

The Victorian model

The model used by the Victorian government has been published in the Medical Journal of Australia. It is peer reviewed. But peer review only tells us that the model is accurate for what it claims to do, not whether or not it is the right model for the decisions being made.

The model is an “agent-based” epidemiological model.

That means that unlike the standard “SIR” model which uses as inputs the number of Susceptible, Infected, and Recovered individuals and explicitly lists equations to describe behaviour and information flows, this one is a computer simulation based on the interaction of agents.

Read more: Victoria now has a good roadmap out of COVID-19 restrictions. New South Wales should emulate it

It runs the simulation over and over again as agents randomly run into each other, and observes how the pandemic progresses. That can be a useful approach, but it is heavily dependent upon a critical assumption: that agents spread the virus by interacting with neighbours, but that (in order to make those interactions computable) the geographical distribution of those agents is pretty smooth.

This means such models don’t divide the population into groups, with the result that, if there is a little bit of the virus somewhere, they predict it will eventually end up everywhere. They invite the conclusion that the best way to stop the virus ending up everywhere is to eliminate the cause of transmission, which is people movement.

Not surprisingly, that is what Victoria has decided to do.

It used a model that is well-calibrated but is based on people moving around, and then decided to stop people moving around because, not surprisingly, in the model that is about the only thing that works.

Read more: Measures to protect community from impact of COVID-19

Is it the right model?

Recall that the premise of the agent-based model is that people interact with neighbours and are linked in a fairly smooth, albeit probabilistic, manner.

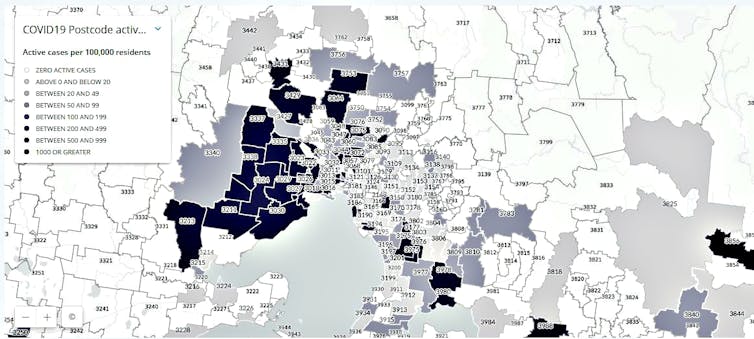

Here is a map of the pattern of outbreaks across greater Melbourne where the strongest lockdowns are in place.

This is the pattern right now, but I have been watching all along and it has been the same throughout.

The pattern suggests that people interact more intensively within their own local areas than in ways that create the same probability of transmission city-wide.

It also suggests that if you are going to have a stringent lockdown and need resources to make that work, there are places where it is more important to put resources than others.

A couple of other things are worth observing.

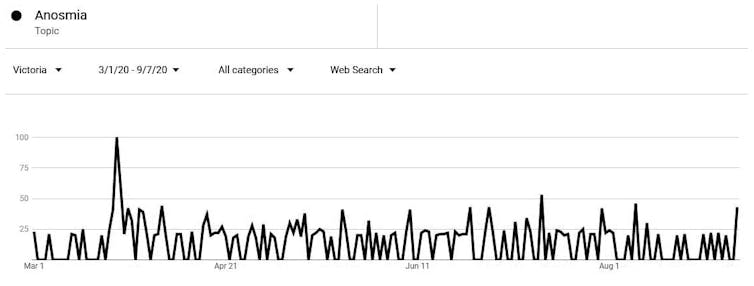

If you check Google Trends data for a common COVID-19 symptom such as anosmia, it shows people have been googling this term at a fairly steady rate since April.

Hopefully, that means there are not large numbers of people the government is missing in tests. (A huge surge in Google searches of common symptoms at a time when new case numbers didn’t appear to be surging might suggest undiscovered infections).

Finally, summer is coming. If allowed to, people will get outdoors more and, from what we know about the coronavirus, that drastically reduces spread.

What should Victoria do?

The government should make public any other modelling it has done and explain how it compares with the model it is using.

There is too much economic cost to additional months of lockdown not to do this.

It is important to take into account network patterns — how people move around in their city and social groups.

Second, the government could make reopening either postcode-based or local government area based. That way the government can monitor whether the low-prevalence areas it reopens first have outbreaks and use that to inform the pace of reopening.

It can use real-time information to update restrictions fortnight by fortnight.

Toronto, Canada where I now live, has a footprint as large as Melbourne and did not treat the entire area as one as it reopened. It has worked reasonably well although the goal pushed in Toronto is a lesser one than elimination.

Read more: Retail won’t snap back. 3 reasons why COVID has changed the way we shop, perhaps forever

Taking the whole of Melbourne as your unit for triggers does not seem to be compatible with the nature of the outbreak.

The most defensible case for it is based on the idea that people regularly travel long distances throughout Greater Melbourne. A middle case is that policing a location-by-location lockdown is harder than policing a city-wide lockdown.

The least defensible case is based on some notion of fairness.

Third, the government should encourage people to be outside as much as possible. No mask mandate outdoors. A more relaxed approach to outdoor gatherings would make the job of enforcing the important directives much easier.

Read more: Should I wear a mask on public transport?

Google mobility reports suggest people are getting out more anyway.

Finally, and I can’t emphasise this strongly enough, test and trace – and quickly! This is the theme of the updated edition of my book and I cover ways of doing it in a pandemic newsletter.

Lockdowns alone won’t get infections to zero. But when cases are low, aggressive identification and isolation of infectious people will.

Victoria is in striking distance of getting infections to zero while avoiding economic pain.

It should double down and do it.

Joshua Gans, Professor of Strategic Management, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.