Frank Bongiorno, Australian National University

If Bob Hawke had never become prime minister, he would still be recalled as a major figure in Australian political and industrial history. As president of the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), Hawke was as instantly recognisable as any pop star. But it is as prime minister of Australia (1983-1991) that he made his greatest mark.

Robert James Lee Hawke was born in Bordertown, South Australia, on December 9 1929, the younger of two sons of Clem Hawke, a Congregationalist minister, and his wife Ellie. The family – minus Neil, who was at boarding school in Adelaide – moved to South Australia’s Yorke Peninsula in 1935. Clem had always doted on Bob, regarding him as “special”. But following Neil’s tragic death from meningitis, Ellie’s passionate love and missionary purpose focused with a new intensity on her remaining son.

The family moved to Perth in 1939. Hawke was educated at the selective Perth Modern School and, from 1947, the University of Western Australia, where he completed degrees in arts and law. He also threw himself into student politics, eventually being elected president of the Guild of Undergraduates.

Clem’s younger brother Albert, a Labor member of the Western Australian parliament and premier from 1953 until 1959, was in these matters his nephew’s mentor and guide.

Bob’s survival of a near-death experience in a motorcycle accident confirmed his parents’ conviction that God had spared their son for a high public purpose. Hawke would abandon Christianity after witnessing poverty in India, but never lost the zeal that dictated he must fully use his talents to make a better world.

While Hawke was at university he met the attractive and intelligent Hazel Masterson, to whom he became engaged in 1950. The following year, Hawke failed to win the Rhodes Scholarship, but was determined to make another bid. Hazel then became pregnant: if they had married – as was usual for a courting couple in such straits – Bob would have been ineligible. Instead, Hazel underwent a traumatic abortion, the first major sacrifice in a marriage that would demand much of her.

Awarded the Rhodes Scholarship in 1952, Hawke travelled to Oxford, where he completed a Bachelor of Letters thesis on Australian wage determination, learned to fly, and broke a world beer-drinking record. Hazel joined him in England.

They married in Perth in 1956 and moved to Canberra, where Hawke had a scholarship to research a doctorate in law at the Australian National University. In 1958, the offer of a position as ACTU research officer led him to abandon his studies and the Hawkes – including Susan, the first of their three children – moved to Melbourne. He proved a pugnacious, knowledgeable and persuasive advocate, becoming a hero in union circles after some notable successes in the Arbitration Commission. In 1963, he narrowly missed winning the federal seat of Corio.

In 1969, Hawke was elected ACTU president, receiving the left’s support in what turned out to be a closely fought contest. During the 1970s, he became a towering figure in national political and industrial life.

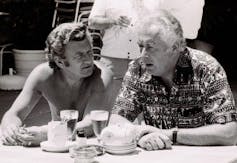

Hawke was peculiarly popular at a time when unions were not, perhaps partly on account of his reputation for having the magic touch in the resolution of industrial conflict. His arched eyebrows and dark wavy hair gave him a striking, handsome appearance seemingly made for television. His educated yet unmistakably Australian speech resonated with the era’s more assertive national identity.

Hawke was also ALP president from 1973 until 1978, and he served as a governor of the Reserve Bank from 1973 until 1980. His relationship with Gough Whitlam was fraught – there was hardly room on the national stage for two egos on this scale – but Hawke was a calming influence after the dismissal, resisting calls for a general strike.

To many, Hawke’s rise to the prime ministership appeared inexorable, yet by the late 1970s there were in place some formidable personal barriers. Hawke was a champion womaniser and boozer. He was an unpleasant drunk. And his widely admired charm and charisma came with a volcanic temper, sometimes on display in his television appearances.

Some flamboyantly boorish behaviour at the 1979 ALP National Conference in Adelaide – involving intemperate criticism of party leader Bill Hayden in the presence of journalists – briefly imperilled his career. But having decided to enter parliament, he gave up the grog. A 1982 biography written by his former lover and future wife, Blanche d’Alpuget, made a clean breast of his personal excesses and family failings. By this time Hawke was the federal member for Wills and shadow minister for industrial relations, having entered parliament at the 1980 election.

Hawke’s pursuit of the federal Labor leadership showed that he was prepared to be ruthless in dealing with an opponent when they stood in the way of what he saw as his destiny. Piece by piece, he and his allies undermined Hayden’s confidence and standing. An unsuccessful bid for the party leadership in mid-1982 was followed by elevation to the leadership in February 1983 after key party powerbrokers lost confidence in Hayden’s prospects, virtually forcing his resignation. Hawke led his party to a comfortable victory on March 5.

In government, he was fortunate to have inherited the Prices and Incomes Accord, finally agreed by the federal ALP and ACTU after Hawke assumed the leadership. The accord committed unions to wage restraint in return for benefits such as Medicare.

Hawke was also endowed with a talented frontbench. But he proved himself a skilled cabinet chair, with a flair for getting the best out of people. His popularity was a valuable asset; Hawke’s approval rating soared, giving weight to his conviction that he had a special relationship with the Australian people.

Hawke was also lucky. The drought ended. The worst of the recession would soon be over. And Australia II’s victory in the America’s Cup seemed as much Hawke’s victory as that of the successful syndicate, after a jubilant prime minister announced that any boss who sacked a worker for not turning up that day was a “bum”.

An emboldened government floated the dollar – in essence, the joint decision of a highly productive partnership with his treasurer, Paul Keating. The government, helped by a High Court decision, prevented the damming of the Franklin River in Tasmania, while Hawke steered the country through a divisive debate about Asian immigration. But in the face of opposition from some states and the mining sector, the government abandoned national Aboriginal land rights legislation, and Hawke’s later commitment to a treaty, similarly abandoned, further damaged the government’s reputation in Aboriginal affairs.

In 1984, Hawke shed public tears over the heroin addiction of his daughter, Rosslyn. He was not at his best in the subsequent election campaign. Hawke won, but had lost some of his shininess.

A balance-of-payments crisis and plunge in the dollar in the mid-1980s provided the backdrop for greater financial stringency and further free-market reform. Welfare carefully targeted those most in need, university fees were reintroduced, and tariffs were lowered. Some public assets were sold.

Critics complained of the abandonment of Labor tradition and criticised Hawke’s closeness to his “rich mates”, along with his alleged subservience to the United States. Electorally, though, Hawke remained a winner, enjoying further victories in 1987 and 1990. No federal Labor leader had won three elections, let alone four.

Hawke’s prime ministership came to grief over his rivalry with Keating and the deterioration of Australia’s economy, culminating in the worst recession since the 1930s. After an unsuccessful tilt at the leadership in mid-1991, Keating defeated Hawke in a ballot shortly before Christmas. Hawke resigned from parliament.

His memoirs, published in 1994, attracted considerable interest not least for his continuing hostility to Keating who was still then prime minister. In 1995, following a divorce from Hazel, he married d’Alpuget. Hawke subsequently worked in the media, pursued a business career and served as chairman of the committee of experts of Education International, a global voice of the teaching profession.

In a 2010 survey of historians and political scientists, Hawke came second, just behind his hero, John Curtin. Hawke’s historical reputation has risen as his record has been viewed in light of the more modest achievements of every one of his successors.

He is survived by his second wife, Blanche d’Alpuget, his children by his first marriage, Susan, Stephen and Rosslyn, six grandchildren, as well as great-grandchildren.

Frank Bongiorno, Professor of History, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.