By C Raina MacIntyre, UNSW; Kerryn Phelps, Western Sydney University; Lisa Maher, UNSW, and Shovon Bhattacharjee, UNSW

After early success in suppressing COVID-19, we are facing a resurgence in Victoria, which is threatening disease control for the whole country.

Outbreaks in northwestern Melbourne, including in public housing tower blocks in inner Melbourne, and now in the twin border towns of Albury-Wodonga, signal a risk of losing our hard-won gains. These gains have already come at a heavy price to the economy and mental health, which is all the more reason to throw everything we can at this resurgence – including widespread use of face masks, as we have seen in other countries such as the United States and United Kingdom.

With 191 new cases announced on July 7, Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews has announced a return to stage 3 restrictions for six weeks from July 9 for metro Melbourne and Mitchell Shire. This means residents will be confined to their homes except for essential trips such as work, medical care, exercise or shopping for essentials. The evidence suggests both sick and healthy people wearing masks will help curb the spread of COVID-19 during this precarious time.

Read more: Coronavirus spike: why getting people to follow restrictions is harder the second time around

Australia is one of the few countries that has suppressed COVID-19 after a peak in disease incidence in late March. The current resurgence, unlike the peak in March which was largely travel-related, has arisen mostly from community transmission, which is a more serious concern.

Health authorities have a range of measures at their disposal, including expanded testing to find all new cases, diligent contact tracing, travel bans, border closures and quarantine of returning travellers. As members of the public, there are five main things we can do to stop the spread: get tested if we have symptoms, download the COVIDSafe App, practise physical distancing, wash our hands often, and wear a face mask.

Why masks help

The most extreme form of physical distancing is a lockdown, already enforced in Melbourne. Keeping at least 1.5 metres away from others also dramatically reduces the risk of COVID-19, even in crowded households. Victorians should think about wearing a mask, especially in indoor spaces like shops or public transport or in outdoor crowds. There may be epidemics developing in other states, so people at risk in those states should think about masks too.

There’s no doubt masks help stop the spread. A recent study commissioned by the World Health Organisation showed that face masks reduce the risk of infection with viruses such as SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, by 67% if a disposable surgical mask is used, and up to 95% if specialist N95 masks are worn, although these are not widely available to the public.

This study prompted the WHO to change its position to recommending community mask use. It had long advised masks should be worn only by sick people to stop them infecting others, although this was perhaps motivated in part by concerns over supplies.

Many countries, perhaps most notably the United States, initially adopted this advice but then began to encourage community-wide mask use when the epidemic began to get out of hand.

Why not in Australia?

Australia has not yet adopted community masking as a tool in the fight against COVID-19. The WHO issued a long list of dangers of mask wearing, including that masks give “a false sense of security, leading to potentially lower adherence to other critical preventive measures such as physical distancing and hand hygiene”.

There is no scientific evidence to support this – in fact, the evidence suggests the opposite. In an illustrative exercise, Italian researcher Massimo Marchiori found people stayed more than twice as far away from him when he wore a mask.

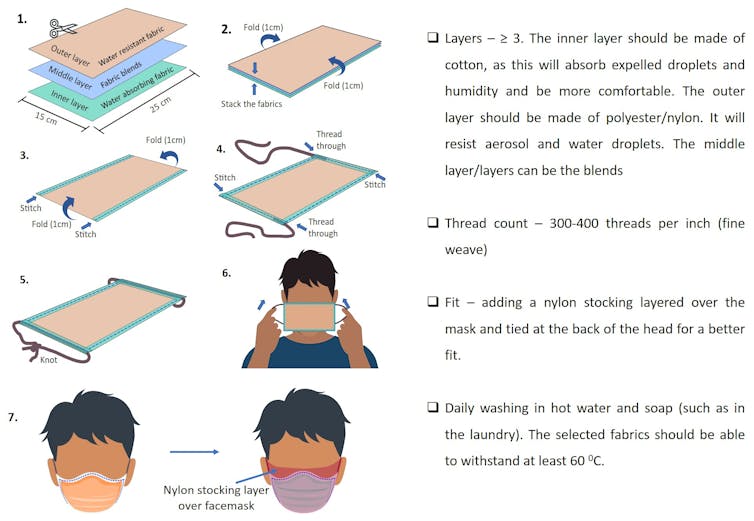

Not all masks are the same, however. For community use, the options are surgical masks and cloth masks. Surgical masks are single-use only and should not be re-used. If they are unavailable or too expensive, you can make an effective cloth version yourself if you follow a few key principles.

Read more: Should I wear a mask on public transport?

Cloth masks can vary widely depending on the material and design – a single or even double-layered mask or bandanna is likely not protective at all.

A cloth mask should have at least three or four layers, including a water-resistant outer layer, a fine weave and high thread count, and should be washed and worn fresh each day. It should fit snugly around your face, or air will flow through the gaps on the sides. A nylon stocking over the top can help.

Research shows a 12-layered cloth mask can be as good as a surgical mask, although you may not have the time or inclination to make a homemade version with 12 layers.

Modelling shows that even a modestly effective mask that delivers just a 20% reduction in viral transmission can successfully flatten the COVID-19 curve. Masks have a double benefit, stopping infected people spreading the virus and protecting uninfected people from catching it.

Given the possibility this coronavirus can also be spread by people without symptoms or even people who have already left the room, handwashing and physical distancing may not be enough. We need every tool at our disposal, and that includes masks.

Read more: Is the airborne route a major source of coronavirus transmission?

Masks can be worn in public or indoors. Surgical masks worn at home can prevent the spread of the coronavirus to family members, which may be worth considering if you live with a health worker or someone else at high risk.

As Melbourne and Australia struggle to regain control of COVID-19, positive promotion of face masks, and simple how-to guides for making, as well as wearing and removing them could be a powerful addition to our armoury. A clear, consistent public health directive in relation to masks is needed now to help avoid longer lockdowns and more draconian measures, and enable safer community activities.

C Raina MacIntyre, Professor of Global Biosecurity, NHMRC Principal Research Fellow, Head, Biosecurity Program, Kirby Institute, UNSW; Kerryn Phelps, Adjunct Professor, NICM Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University; Lisa Maher, Professor, Faculty of Medicine, UNSW, and Shovon Bhattacharjee, PhD Candidate, The Kirby Institute, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Photo by Gustavo Fring from Pexels